Recent Research into the Effects of Obesity on Aging

It is no big secret that being overweight will harm your future prospects for health and longevity. The more visceral fat tissue, the worse off you will be. Since it is somewhat easier to be in denial on this topic than it is to lose significant amounts of weight, there are a lot of people out there in some state of denial regarding the harm they are doing to themselves. This situation was not made better by flawed epidemiological studies in past years suggesting that overweight people had lower mortality rates in later life. Those studies have since been comprehensively torn apart and their flaws dissected in detail.

People lose weight when they are in the later stages of age-related disease, and thus we must discard every study that failed to distinguish between (a) people who are in a normal weight range because they are dying and (b) people who are in a normal weight range and essentially as healthy as they can be for their age group. Sadly, that is a great many studies, including those that have been adopted as a security blanket by that portion of the public at large who wish to be told something other than that they should strive to lose weight or suffer the consequences. In reality, every increment of visceral fat tissue adds to the risk of age-related disease and early mortality.

Of the two studies I'll point out here, the first is representative of more modern work on the consequences of being overweight, in which the authors take more care with the data, and their conclusions conform to the present consensus. The second is an interesting addition that might be considered to support the idea that the best metric of harm is the amount of excess fat multiplied by how long that level of fat is sustained. So being fat for a few years is bad, and leaves a lasting footprint on your future risk of age-related disease, but being fat for a decade or two is far worse. Like smoking, the best time to stop is always now. Continuing as you are will only make matters worse.

Study of 500,000 people clarifies the risks of obesity

Elevated body mass index (BMI) - a measure of weight accounting for a person's height - has been shown to be a likely causal contributor to population patterns in mortality, according to a new study. Specifically, for those in UK Biobank (a study of middle to late aged volunteers), every 5kg/m2 increase in BMI was associated with an increase of 16 per cent in the chance of death and specifically 61 per cent for those related to cardiovascular diseases.

While it is already known that severe obesity increases the relative risk of death, previous studies have produced conflicting results with some appearing to suggest a protective effect at different parts of the spectrum of body mass index. Until now, no study has used a genetic-based approach to explore this link. The findings which link body mass index and mortality, confirm that being overweight increases a person's risk of death from all causes including cardiovascular diseases and various cancers.

The team applied a method called Mendelian randomization, a technique that uses genetic variation in a person's DNA to help understand the causal relationships between risk factors and health outcomes - here mortality. This method can provide a more accurate estimate of the effect of body mass index on mortality by removing confounding factors, for example, smoking, income and physical activity, and reverse causation (where people lose weight due to ill health), which could explain the conflicting findings in previous observational studies.

Weight Cycling Increases Longevity Compared with Sustained Obesity in Mice

Despite the known health benefits of weight loss among persons with obesity, observational studies have reported that cycles of weight loss and regain, or weight cycling, are associated with increased mortality. To study whether weight loss must be sustained to achieve health and longevity benefits, we performed a randomized controlled feeding study of weight cycling in mice.

In early adult life, obese mice were randomized to ad libitum feeding to sustain obesity, calorie restriction to achieve a "normal" or intermediate body weight, or weight cycling (repeated episodes of calorie restriction and ad libitum refeeding). Body weight, body composition, and food intake were followed longitudinally until death. A subsample of mice was collected from each group for determination of adipose cell size, serum analytes, and gene expression.

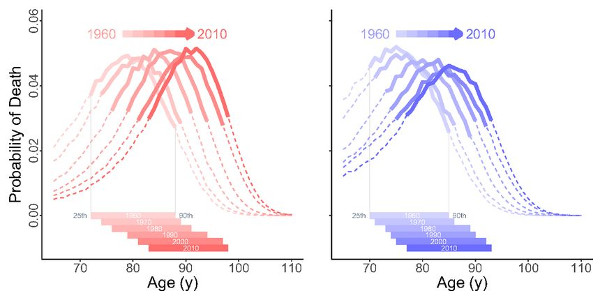

Weight loss significantly reduced adipose mass and adipocyte size in both sexes, whereas weight cycling animals regained body fat and cell size during refeeding. Sustained weight loss resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in mortality compared with ad libitum feeding. In conclusion, weight cycling significantly increased life-span relative to remaining with obesity and had a similar benefit to sustained modest weight loss.