Today I stumbled over a popular press article on the topic of longevity science, in which a fair amount of attention is given to Aubrey de Grey and the SENS Research Foundation vision for rejuvenation biotechnology. Like most such articles it is a view from an individual who, though a scientist himself, stands far outside the field of aging research - just like much of the world he is looking in with limited knowledge, trying to make sense of it all, in search of truth from a position of ignorance.

This struggle, the search for truth in a field in which you will never personally know enough to verify any significant detail for yourself, is one of the defining characteristics of the human condition. We have the urge to know in the moment that we encounter a new assertion, but we cannot justify spending the years it would take to know ourselves, versus accepting a secondhand truth that may or may not in fact be correct. It is frequently a challenge even to understand how great or little is the uncertainty of any claim we come across. This has always been the case, but now that we are all connected in a vast web of communications, superficial summaries of every aspect of human knowledge at our fingertips, the quest for truth is a mouse click away every moment of the day, and we accept all too much of what we see simply because we do not have the time to do otherwise.

This is compounded by the fact that some fields of science are in tumult, experienced researchers in public dispute over vital theories. It is a sign of the times, of accelerating progress. Astrophysics and cosmology were some of the first to benefit from the computational revolution and haven't stood still for long enough to catch a breath in decades; what a student learns in school is out of date within a few years. The life sciences are now in much the same boat, and the study of aging in fact has a great in common with the study of astrophysics in that (a) technology now enables theorizing to proceed far more rapidly than the collection of new and useful data, (b) the problem space is vast, the existing volume of data huge, and the unknown details yet to be filled in even larger, which means that (c) many theories can be made to fit the data that we do have, these theories are multiplying rapidly, and proving or disproving them is a slow process indeed. The junk builds up alongside the specks of gold, and sifting becomes an ever more laborious process.

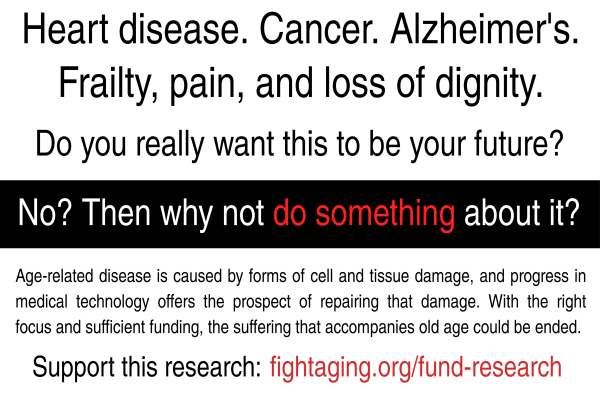

This all matters far more for aging than for the study of the observable universe beyond the Earth because we are operating under a deadline. We're all aging, and if the research community chases the wrong theories for the next decade or two, meaning those that require expensive work for marginal benefits, that will make the difference between a good life and a painful death in old age for most of us. Pure science is all well and good, but therapies are needed, and pushing for meaningful development as fast as possible requires a slightly different focus from that of the standard scientific model of learning everything there is to know about the system in question before taking action. One other way in which aging research is similar to astrophysics is that very little of it has any connection with development of new technologies: most aging research groups are entirely happy with their focus on gathering data and nothing more.

In any case, the author of this article is some places self-aware of the issue of ignorance and truth, while in others he hasn't looked deeply enough. He could have looked at the scientific advisory board of the SENS Research Foundation today to see the heavy-hitters in the scientific community who are on board rather than simply quoting some of those who opposed SENS as a research strategy in public a decade ago, to pick one example. How do you sift for truth? You look for networks of people who have taken the time to run the analysis, who have the specialized knowledge to say one way or another. There are few who steadfastly claim SENS is the wrong road these days, and they are largely in the programmed aging community, not the same folk as those who turned up their noses more than ten years ago, long before SENS and SENS-like programs had produced numerous confirmations of the potential of this research strategy.

Since then we've seen examples of senescent cell clearance, mitochondrial repair through allotopic expression is in late stage development for the treatment of mitochondrial disease, work on therapies for senile systemic amyloidosis is moving ahead, and so forth. It's a different world now. All this information is out there if you care to look, or ask those who have been following along all this time:

The God quest: why humans long for immortality

Myths live on by disguising themselves in the apparel of modernity. So it is fully to be expected that immortality today is a business offering to tailor clients' diet regimes, that it is expounded at conferences in PowerPoint presentations, that it announces itself with words such as "telomere extension" and "immune regulation". This is distressing to serious biogerontologists, who worry that funding of their careful work on age-related disease and infirmity will seem boring in comparison to supporting folks who promise to let us live for ever. They are right to be concerned but sadly theirs will ever be the fate of scientists working in a field that touches on fabled and legendary themes, where both calculating opportunists and well-meaning fantasists can thrive. Age-related research until recently has been rather marginalised in medicine, and the gerontologist Richard Miller of the University of Michigan suggests one reason for this: "Most gerontologists who are widely known to the public are unscrupulous purveyors of useless nostrums."

It is surprising, perhaps alarming, that we know so little about ageing. We get old in many ways. For instance, some of our cells just stop dividing - they senesce. While this shutdown stops them becoming cancerous, the senescent cells are a waste of space and may create problems for the immune system. Cell senescence may be related to a process called telomere shortening: repeated cell division wears away the end caps, called telomeres, on the chromosomes that contain our genes. Although shortened telomeres seem to be related to the early onset of age-related disease, the relationship is complex. It is partly because cancer cells are good at regenerating their telomeres that they can divide and proliferate out of control. Cells also suffer general wear and tear because of so-called oxidative damage, in which reactive forms of oxygen - an inevitable by-product of respiration - attack and disrupt the molecules that sustain life. This has made "antioxidants" such as Vitamins C and E, and the compound resveratrol, found in red wine, buzzwords in nutrition. But the effects of oxidative damage and antioxidants are still poorly understood.

These factors and others can interact with each other in complex ways. A group of UK experts called the Longevity Science Panel, funded by the insurers Legal & General, concluded in a 2014 report: "There is little consensus on which mechanisms of ageing are the most important in humans." Biogerontologists don't even agree about whether the ageing process itself is best considered as a single effect, or many.

Aubrey de Grey genuinely seems to believe not only that he is on to something but that his ideas are of humanitarian importance. He is nothing if not sincere in thinking that to slow and ultimately reverse ageing is an obligation that science is failing dismally to fulfil. He regards old age as a disease like any other: it is scandalous, he says, that it kills 90 per cent of all human beings and yet we are doing so little about it. De Grey calls his quest a "crusade to defeat ageing", which he regards as "the single most urgent imperative for humanity". Death, he says, "is quite simply repugnant", and he equates our acceptance of it in elderly people with our past casual acceptance of the slaughter of other races.

How does de Grey think we will stop our bodies from ageing? He proposes a seven-point plan called SENS (Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence) that, in his view, picks off all the processes by which our cells decline, one by one. We can get rid of unwanted cells, such as excess fat cells and senescent cells, by training the immune system or triggering the cells into eliminating themselves. We can suppress cancer by silencing the genes that enable cancer cells to repair their telomeres. We can avoid harmful mutations in the handful of genes housed in our energy-generating cell compartments called mitochondria by making back-up copies, to be housed in the better-protected confines of the cell's nucleus, where the chromosomes reside. We can find drugs that inhibit the degradation of tissues at the molecular level. And so on.

His detractors point out that almost all of these plans amount to saying, "Here's the problem, and we'll find a magic ingredient that fixes it." If you think there are such ingredients, they say, then please find just one. He is looking. With inherited wealth and venture capital backing from the likes of PayPal's co-founder Peter Thiel, de Grey maintains an institution in Mountain View, California, called the SENS Research Foundation, with laboratories to investigate his proposals. But he insists that the criterion of success isn't a steadily increasing longevity in model organisms, because SENS is a package, not a series of incremental steps. No one criticised Henry Ford, de Grey says, because the individual components of his cars didn't move if burning petrol was poured on them.

The hope of medical immortality may be false but it raises moral and philosophical questions. Is there something fundamental to human experience in our mortality, or is de Grey right to see that as a defeatist betrayal of future generations? Do we value life precisely because it passes? And is there an optimal span to our time on earth? These are pertinent questions for even the most sober gerontologists, because the truth is that the ageing process can be slowed, and we can expect to have longer lives in the future and to remain well and active for more of that time.

For instance, it has been known for decades that rats and mice live longer, and stay healthy for longer, when given only the quantities of a well-balanced diet that they need and no more. This so-called caloric restriction seems to slow down ageing in a wide range of tissues. No one knows why, but it seems to point to a common mechanism of ageing that extends between species. Some researchers think that with caloric restriction it might be possible to extend mean human lifespans to roughly 110 years. Others aren't persuaded that caloric restriction would be effective at all for slowing ageing in human beings - studies on rhesus monkeys have been inconclusive - and they point out that it is a bad idea for elderly people.

Couldn't we just make an anti-ageing pill? There are candidates. The drug rapamycin, which is used to suppress immune rejection in organ transplants and as an anti-cancer agent, also has effects on ageing. It stops cells dividing and suppresses the immune system - and increases the lifespan of fruit flies and small mammals such as mice. But it has nasty side effects, including urinary-tract infections, anaemia, nausea, even skin cancer. Other researchers think that the answer lies with genetics. The genomics pioneer Craig Venter, whose company Celera privately sequenced the human genome in the early 2000s, recently launched Human Longevity, Inc together with the spaceflight entrepreneur Peter Diamand. It aims to compile a database of genomes to identify the genetic characteristics of long-lived individuals. Whether Venter will find genes responsible for the exceptional longevity of some individuals, and whether they would be of any use for extending average lifespan, is another matter. "His approach has some serious conceptual limitations," the Michigan gerontologist Richard Miller tells me. "I think he's radically overestimating the degree to which the ageing process is modulated by genetic variation."

To read one script, we are on the cusp of a revolution in ageing research. Google has recently created the California Life Company, or CALICO, which seems to be seeking life-extending drugs. The hedge-fund billionaire Joon Yun has launched the $1m Palo Alto Longevity Prize to bring about the "end of ageing", so that "human capacity would finally be fully unleashed". But the Longevity Science Panel, composed of scientists rather than venture capitalists, had a much more sobering message. To get a substantial increase in lifespan - an extra decade or so, say - we would need to find ways of slowing the ageing rate by half (which the panel deemed barely plausible given the current knowledge) and apply that treatment throughout a person's life from an early age. If you're already middle-aged today, even major breakthroughs are barely going to make any difference to how long you will live.

Researcher Richard Miller is a good example for the complexity of positions in aging research. He is an outspoken opponent of SENS research, yet he and I are basically on the same page when it comes to the poor value of genetic research into variations in human longevity. When you look at a given researcher's position, it isn't just a matter of for and against, or a few large camps of opinion, but rather in a field this complex you really have to make a list of twenty or so nuanced opinions and run through them all to check boxes. Everyone has a slightly different overall take, and while many overlap to a considerable degree, there is always something to disagree on. This state of affairs will continue until good data arrives to support one course forward above the others - which I would expect to happen when the first robust SENS-like repair therapies in mice demonstrate unequivocal extension of healthy life span. We're somewhere near that point for senescent cell clearance, I think, but there is much more to come yet.