Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS) is a detailed plan for curing human aging. It's detailed, thorough and firmly based on established experimental work in the various relevant areas of biology. So, you may well ask, where's the catch? Why, on all the many documentaries on aging that remain so popular, don't my colleagues come out and advocate the same work that I advocate?

Copyright © Aubrey de Grey. This is an edited version of the original piece appearing at the SENS website.

Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS) is a detailed plan for curing human aging. It is an engineering project, in the same way that medicine is a branch of engineering. The key to SENS is the appreciation that aging is best viewed as a set of progressive changes in body composition at the molecular and cellular level, caused as side effects of essential metabolic processes. These changes are best thought of as an accumulation of "damage," which becomes debilitating and eventually fatal above a certain threshold. The traditional gerontological approach to life extension, namely to try to slow down this accumulation of damage, is a misguided strategy, firstly because it requires us to improve biological processes that we do not adequately understand, and secondly because it can - even in principle - only slow aging rather than reverse it. An even more shortsighted alternative is the geriatric approach: to try to stave off pathology and death in the face of accumulating damage. This is a losing battle because the continuing accumulation of damage makes pathological outcomes more and more inevitable.

The engineering (SENS) strategy is not to interfere with metabolism as such, but to repair or obviate the accumulating damage - thereby indefinitely postponing the age at which it reaches pathogenic levels. You can read much more about SENS at my website, in papers aimed at both a scientific and more general audience. The SENS strategy as I have described it purports to have all the characteristics that should make it persuasive: it's detailed, thorough and firmly based on established experimental work in the various relevant areas of biology. So, you may well ask, where's the catch? Why, on all the many documentaries on aging that remain so popular, don't my colleagues come out and advocate the same work that I advocate?

There are three main reasons why most mainstream gerontologists remain so conspicuously absent from the growing band of vocal advocates of the SENS approach to curing aging. These reasons are all understandable, but given the importance of the problem and the key role that senior specialists play in determining public opinion and hence public policy, I feel that none is a legitimate excuse.

The central reason is simple ignorance of the relevant science. Biology -- even human biology -- is a very big subject, so nobody can hope to understand it all in depth. Thus, biologists restrict themselves to understanding in depth a rather narrow subset of biology and they trust each other to focus on the other areas. Unfortunately, this strategy is utterly reliant on having a good instinct for when new research turns a formerly irrelevant field of biology into a field that is suddenly very relevant indeed. Most of the areas that I have introduced into the biology of aging have so far received only limited attention because most biogerontologists don't instinctively see how they could be useful.

The second reason is really subsidiary to the first, in that its importance is in sustaining the ignorance I just referred to. The progress of ideas always has enormous inertia, on account of the emotional, intellectual and financial investment on the part of those who hold conventional views. Scientists, like others, find it difficult to write off that investment and embrace a new paradigm even when the argument for that new paradigm is very comprehensive. This manifests as a reluctance to consult relevant scientific literature, or even to entertain the idea that such literature is relevant in the first place. It also manifests as a preference for avoiding overt debate on such matters, since any such debate opens up the risk of being forced to acknowledge the superiority of the new paradigm. None of this is conscious, but it is a very powerful force opposing progress. In this case, the idea that reversing aging might be easier than slowing it down a bit is so counter-intuitive that many of my colleagues are inclined to dismiss it out of hand before taking the time to look at my argument in detail.

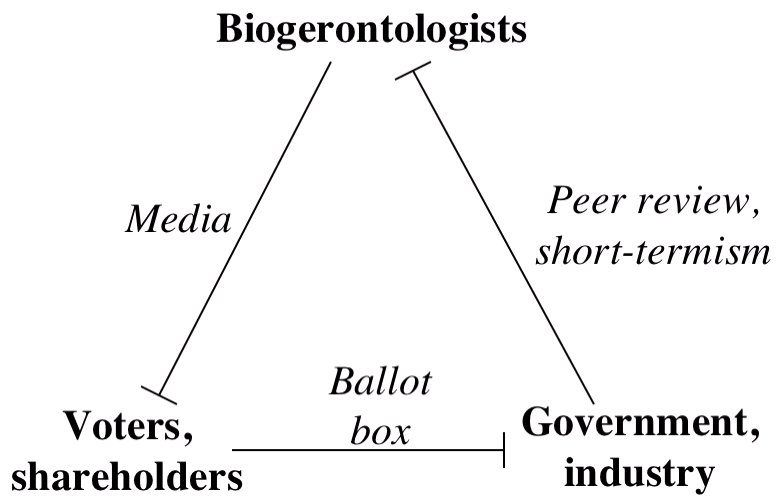

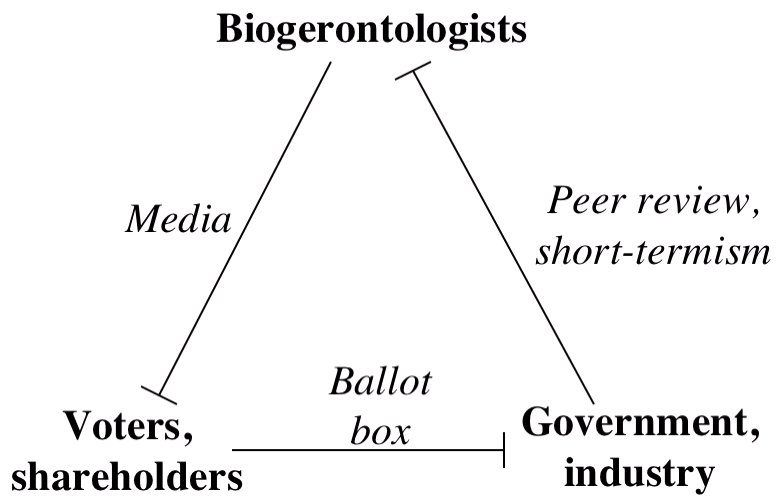

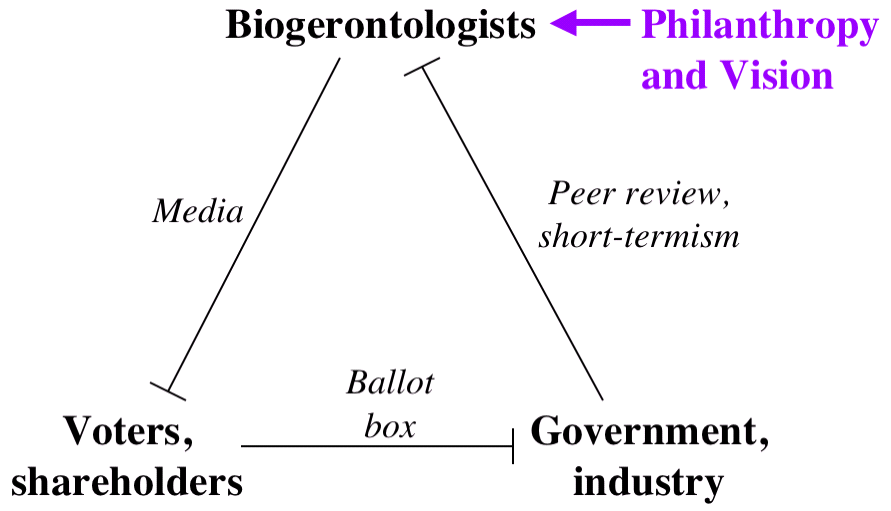

The third reason that my colleagues mostly don't say what I say is political. Scientists prefer to promote and discuss what they are working on. They aren't so keen to tell people that they would be working on something altogether more interesting or ambitious if only their funders had the imagination and courage to sponsor it, because that's a quick way to lose funding. Now, you might ask, why are funders so unambitious? In industry it's because of the dominance of short-term views: shareholders reward companies that can make money quickly and certainly with boring products, and so these companies will do so in preference to taking greater risks on ambitious products - even if the potential rewards are far greater. In the public sector, funders don't want to be perceived to be wasting taxpayer money on blue-sky work with no chance of success. So, the root problem here is the pessimism of voters. But, of course, that pessimism is due precisely to the public face that senior biogerontologists put on their research...

This "triangular logjam" is the fundamental obstacle to obtaining more money for life extension research.

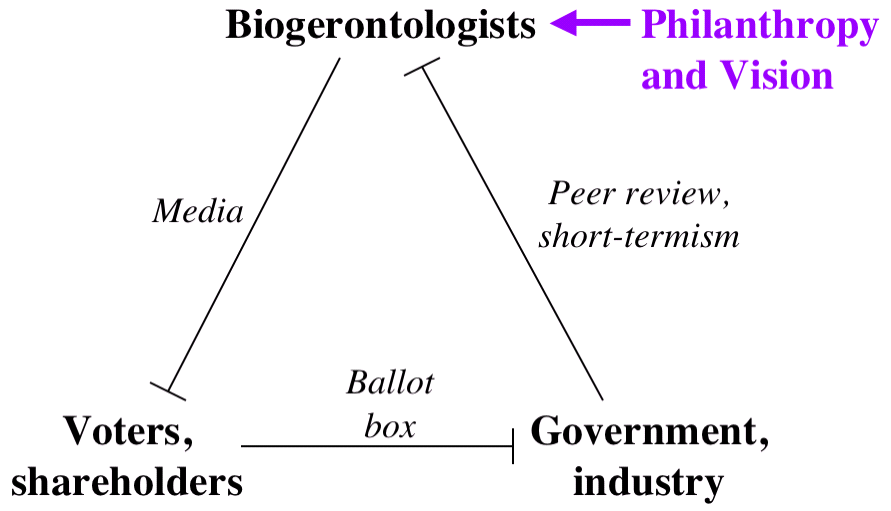

The logjam can be unblocked at any corner. My work is focused on the "biogerontologists" corner because I know them all personally and because they are few in number. The quickest way to change the minds of scientists regarding research priorities, however, is to remember that scientists will do anything interesting for money. Hence, an alternative supply of funds is a solution:

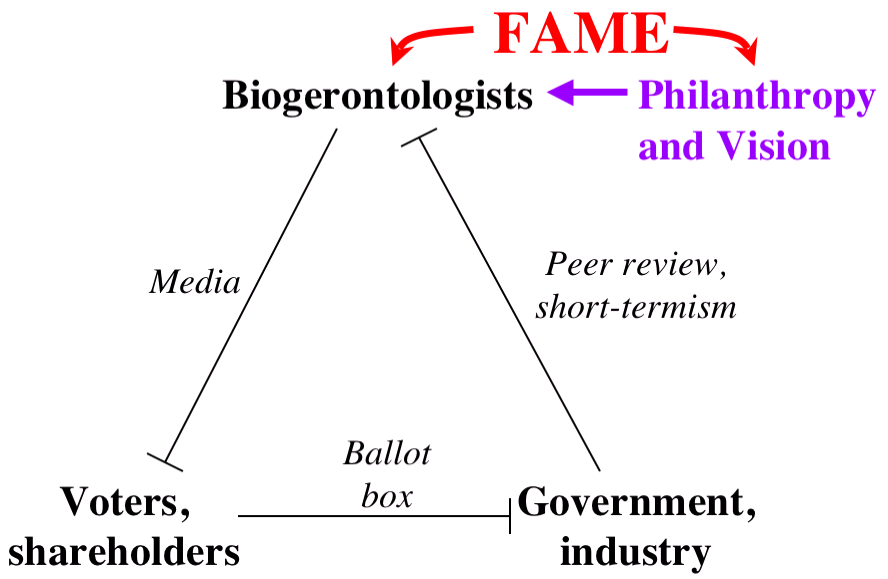

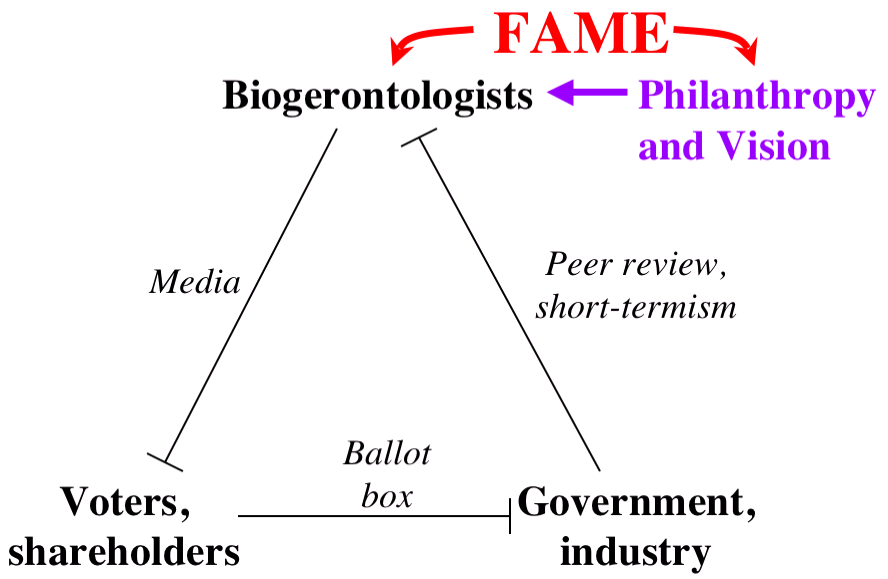

Finally, both the scientists and the prospective philanthropic funders may be encouraged to take the plunge if a bit of publicity comes their way:

This publicity method is one motivation for the Methuselah Mouse Prize for anti-aging research.

In conclusion I should stress that many of my colleagues, on reading or hearing the castigation of them that I have rehearsed above, would say that in fact there is a wholly responsible reason why they are cautious in their public predictions of the rate of progress: namely, they think it would be irresponsible to raise hopes and create unwarranted optimism. My answer is that experts can mislead the public just as powerfully by silence as by speaking out, if the public is predisposed to be pessimistic on the scientific issue in question - as they certainly are in this case. I therefore claim that biogerontology is a case where the general rule of not getting people's hopes up unduly is being taken too far.